...someone got one last night. A forty-

something year old liver. From a forty-

something year old man who collapsed inexplicably at home. He was rushed to an area hospital, but the point of irreversible damage had been reached. He’d ruptured an aneurysm in one of the blood vessels of his brain. He was pronounced brain dead by two independent neurologists. His family came to a consensus, one that I’m sure was difficult, to donate his organs.

This is where I come in. About four times a month, I take a 24 hour shift of call for a group of transplant surgeons…I basically carry my pager around in anticipation of a call from one of the surgeons who needs an assisting surgeon to help “procure” organs should a donor come up. Two sets of hands are needed to procure livers, kidneys and pancreases. So I am the second set of hands, the assisting surgeon. I take these calls for a number of reasons. One. The two-year research hiatus from my surgery residency that I started in July doesn’t include the usual hustle and bustle of hours on end in the operating room. It involves lots of reading, lots of “researching,” lots of data collection, lots of writing, and only some interaction with patients (to the extent that I need to recruit them into clinical trials). But no operating. So as not to get OR-sick (like homesickness…well...kinda) I decided to do this work with the transplant surgeons. Two. It’s extra pay. If there is anything that most people don’t know about medical education…it’s that it’s expensive. I’m in more debt than I care to acknowledge. And if there’s anything that most people don’t know about surgical residency, it’s that it doesn’t pay well. So the extra money helps. Three. It’s interesting. I do not aspire to be a transplant surgeon when I grow up to be a full on, board certified, grade A beef surgeon. (Why, is a whole other story.) However, the idea that organs can be removed from one person and placed into another is something that will never cease to amaze me. Four. It holds a near and dear place in my heart. The Brit’s sister and father both died untimely deaths and both were organ donors. This all happened well before I started dating The Brit, and yet, I feel like they are among us, in the living, in a way. Strange, perhaps. And yet, strangely true.

It’s a bizarrely sublime thing, transplant surgery. Sublime because it gives people a second chance…diabetics with such horrifically far gone disease that their kidneys have failed, recovering alcoholics whose livers have been exhausted, countless others with countless other diseases. Second chances. A beautiful concept. And yet bizarre…because it’s incredibly morbid. Survival of one relies upon the death of another. It’s the juxtaposition of loss and gain, bad luck and good luck, death and life, sadness and overwhelming joy. It forces the collision of two worlds (that of the donor and the recipient) that would have likely otherwise never intercepted.

Actually, it forces the collision of a lot more than just two worlds. One donor tends to provide organs to multiple recipients. And the production that’s involved before the “match” involves a whole cast of behind-the-scenes individuals. On the donor side, there’s the physician who calls the transplant network who sends out the transplant coordinator. Often perceived as the “vultures” that hover around the “almost dead” in our ICU’s, these people often get the hard end of the deal. They’re just doing their job, but to the friends and family members of the potential donor it’s appalling what they’re asking…imagine your brother’s just been hit by a car and 24 hours later he’s pronounced brain dead and some person you’ve never met quietly approaches you with a card asking you to consider giving away his body parts. You can see how one might think that person an insensitive, intrusive vulture. But time, as the potential recipient knows, is of the essence. For the family of the donor, it’s never a good time. For the recipient, there’s never a better a time. On the recipient side there’s the physicians and nurses and social workers providing care for that person until they are transplanted, IF they are lucky enough to get transplanted. That brings us to the list, and all the people that go into making the list of who deserves which organ and how urgently. Toughy. Glad that’s not my job. I just show up when the powers that be have found that the blood types and body types (size does matter) between unfortunate person A and fortunate person deserving of second chance B are compatible. I show up at the hospital and there is a van waiting to take me and the other surgeon to whichever hospital the donor is located. If the donor is close, we drive. If not, we fly. We travel with all that we need…our special surgical instruments and catheters, the “coolers” in which we plan to bring each organ back, cold preservation fluid. It’s a big production.

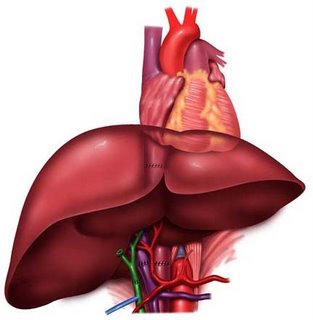

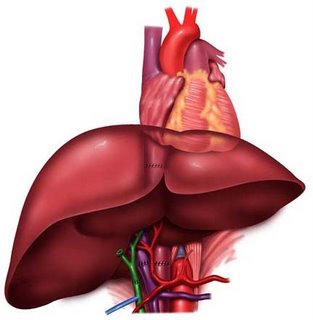

Now for the operation. The procurement of the organs. The “harvest” as some casually refer to it (though, truthfully, that sounds a bit too agricultural for me). As the donor was wheeled into the OR last night, I took a good look, as I always do, at my patient. Looking past the tangle of life-sustaining IV’s, catheters, and endotracheal tube, I saw an otherwise normal looking 40-something year old man. But, poor guy, he wasn’t normal. Heart beating. Lungs oxygenating his blood, ventilating off the carbon dioxide (with the help of the ventilator). Kidneys making urine, which was spilling out of a catheter into a collection bag. But no “life.” Not a whiff of sedating drugs in his system and he was completely nonresponsive. Pupils fixed, dilated. No motor responses. No reflexes. No independent respiratory drive. For as many times as I’ve assisted in a procurement, the bizarreness of operating on a “patient” like this never seems to pale for me. To me, a “patient” is a person who I’m treating in some way, caring for, helping, healing. (Isn’t that what we all go into medicine to do? “Help” people?) Big picture, sure, we’re helping someone, probably many someones, with his organs. But zoom in on the picture, in that OR last night, and we were hardly “treating” this 40 something year old guy. Nothing, except maybe a time traveling machine, could help him now. And perhaps that’s how we justify removing his organs. And remove them we did. Patient prepped and draped, Dr. HG and I stood down by the abdomen while two heart surgeons, who’d flown in from Washington State, stood up by the chest. They made their incision first, down the middle of the chest, and we connected the top of our midline abdominal incision with the bottom of their sternal incision. Sternum sawed open. Retractors in. And there…full visibility of all that is normally tucked away under skin and bone. It’s anatomy more beautiful than DaVinci was ever able to capture in all of his pencil drawings. The reasons I became a surgeon are many, but anatomy is certainly up there. The heart surgeons went about their business of getting ready to take the heart, while we went about the business of taking the liver and kidneys. Lots of careful dissection. Identification of important structures. Catheters into the aorta and the inferior mesenteric vein. Clamp. Clamp. Preservation fluid is run through the catheters to flush the liver and kidneys out (numerous reasons for the preservation fluid, one of which is to remove the blood which would clot). Liver out. Kidneys out. Each into their own little basin with icy preservation fluid. Dr. HG steps away from the operating table to a separate back table where he readies the organs for their respective destinations. I am left with the patient, who by now is heartless, liverless and kidneyless. All monitors are off. The anesthesiologist is gone. It is an eerily silent moment in the operation. And I still have work to do. In the bothersome quiet, I dissect out the iliac arteries and veins (they are used as “extensions” for

Now for the operation. The procurement of the organs. The “harvest” as some casually refer to it (though, truthfully, that sounds a bit too agricultural for me). As the donor was wheeled into the OR last night, I took a good look, as I always do, at my patient. Looking past the tangle of life-sustaining IV’s, catheters, and endotracheal tube, I saw an otherwise normal looking 40-something year old man. But, poor guy, he wasn’t normal. Heart beating. Lungs oxygenating his blood, ventilating off the carbon dioxide (with the help of the ventilator). Kidneys making urine, which was spilling out of a catheter into a collection bag. But no “life.” Not a whiff of sedating drugs in his system and he was completely nonresponsive. Pupils fixed, dilated. No motor responses. No reflexes. No independent respiratory drive. For as many times as I’ve assisted in a procurement, the bizarreness of operating on a “patient” like this never seems to pale for me. To me, a “patient” is a person who I’m treating in some way, caring for, helping, healing. (Isn’t that what we all go into medicine to do? “Help” people?) Big picture, sure, we’re helping someone, probably many someones, with his organs. But zoom in on the picture, in that OR last night, and we were hardly “treating” this 40 something year old guy. Nothing, except maybe a time traveling machine, could help him now. And perhaps that’s how we justify removing his organs. And remove them we did. Patient prepped and draped, Dr. HG and I stood down by the abdomen while two heart surgeons, who’d flown in from Washington State, stood up by the chest. They made their incision first, down the middle of the chest, and we connected the top of our midline abdominal incision with the bottom of their sternal incision. Sternum sawed open. Retractors in. And there…full visibility of all that is normally tucked away under skin and bone. It’s anatomy more beautiful than DaVinci was ever able to capture in all of his pencil drawings. The reasons I became a surgeon are many, but anatomy is certainly up there. The heart surgeons went about their business of getting ready to take the heart, while we went about the business of taking the liver and kidneys. Lots of careful dissection. Identification of important structures. Catheters into the aorta and the inferior mesenteric vein. Clamp. Clamp. Preservation fluid is run through the catheters to flush the liver and kidneys out (numerous reasons for the preservation fluid, one of which is to remove the blood which would clot). Liver out. Kidneys out. Each into their own little basin with icy preservation fluid. Dr. HG steps away from the operating table to a separate back table where he readies the organs for their respective destinations. I am left with the patient, who by now is heartless, liverless and kidneyless. All monitors are off. The anesthesiologist is gone. It is an eerily silent moment in the operation. And I still have work to do. In the bothersome quiet, I dissect out the iliac arteries and veins (they are used as “extensions” for when the liver is sewn into the recipient, as sometimes, the vessels going into and out of the donated liver aren’t quite long enough). The vessels go in their own container of preservation fluid. And then, with two long sutures, I close the incision. Drapes off. Except for the incision, the slight concavity in his abdomen, and the silent monitors, not much looked different. But it was. Much different.

when the liver is sewn into the recipient, as sometimes, the vessels going into and out of the donated liver aren’t quite long enough). The vessels go in their own container of preservation fluid. And then, with two long sutures, I close the incision. Drapes off. Except for the incision, the slight concavity in his abdomen, and the silent monitors, not much looked different. But it was. Much different.

When I got home last night, I looked up the American Heritage Dictionary definition of patient:

pa·tient n. 1. One who receives medical attention, care, or treatment. 2. Linguistics. A noun or noun phrase identifying one that is acted upon or undergoes an action. Also called goal. 3. Archaic. One who suffers.

Our donor did suffer an untimely death. A ruptured cerebral artery aneurysm…death was his unfortunate fate, with or without his organs. Perhaps his family will suffer less knowing that he helped so many. I hope so. Now begins the afterlife.